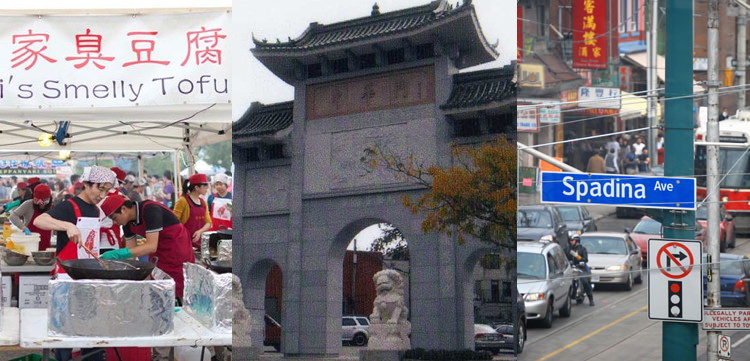

Chinatown Here, There and Everywhere

/By Chantal Braganza

Sweet shops, cell phone stores, restaurant strips, entire malls. If you think the idea of an ethnic aisle is a weird and kind of reductive category to use in a grocery store, consider that it’s one of the only ways we have to talk about retail set up by “newcomer” populations years, even decades, after they’re no longer newcomers.

Does being in a certain neighbourhood render a store “ethnic retail”? How do such centres work and does it matter where they’re located? Even if the terminology is a bit limiting, these questions do have merit, which is why I sought out one of the country’s foremost researchers on the topic.

When Xhixi Zhuang moved to Toronto from Guangzhou, China 15 years ago, she was particularly taken with the crosstown sights from the window of the Carlton streetcar.

“You can see so many neighbourhoods in the inner city if you ride from High Park to Main Street: Little Portugal, Little Italy, Kensington Market, East Chinatown,” says Zhuang, now an assistant professor of urban and regional planning at Ryerson University. “You see 100 years of immigration history happening in Toronto, how communities adapt these spaces to new uses, and how they adapt their identities to the existing neighbourhood.”

In 2008, as a PhD candidate in urban planning at the University of Waterloo, Zhuang dedicated her thesis to the study of the retail strips in such places, from Gerrard Street East’s Little India Bazaar and East Chinatown to St. Clair West’s Corso Italia, as well as Markham’s Pacific Mall. Through these four case studies, she learned about the development issues facing mainstreet and mall-format retail. She also examined the level of involvement by local planners and politicians, and even business owners themselves.

Some issues were specific to place or culture. Little India’s immigration history is more recent than East Chinatown’s, for example, while Corso Italia-area shopkeepers struggled with disruption from the St. Clair streetcar right-of-way construction in recent years. But downtown ethnic retail strips also had a few things in common.

“Chinatowns and Little India bazaars in the inner city have a symbolized meaning. They’re kind of like the business card of the city, and the city uses them to sell its diversity,” Zhuang says.

Their relationship with City Hall also often looks similar. “Both the Spadina and Gerrard Chinatowns are designated as BIAs,” she says, referring to the organizations of local commercial property owners and tenants known as Business Improvement Areas. “They raise funds on their own but also work in partnership with and receive support and resources from the city. There’s the partnership of the private ownership of the business, and the public ownership of the space.”

“You see 100 years of immigration history happening in Toronto, how communities adapt these spaces to new uses, and how they adapt their identities to the existing neighbourhood.”

Unlike their counterparts downtown, most outlying ethnic retail centres, like the South Asian strip malls near Airport Road or Koreatown North at Yonge and Sheppard, aren’t actively marketed as tourist attractions. (Markham’s Pacific Mall is an exception.) The way people operate, shop at and sometimes live in those spaces is also quite different, Zhuang argues. She recently launched a study funded by the federal government’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council to examine Chinese and South Asian retail clusters in Mississauga, Brampton, Scarborough, Richmond Hill and Markham.

While her two-year study is still in the fieldwork stage, she points to certain characteristics that set these outlying retail neighbourhoods apart from their inner-city cousins.

For one thing, the business space rental and ownership models are different. “In Chinatown, many of the shops are mom-and-pop businesses,” she says. “But in the suburbs, a lot of these retail shops in the malls are under condominium ownership—individual owners can purchase a unit instead of rent it from the developer, or lease it out for a profit.”

Another significant difference, particularly in mall developments, is that the anchor tenants aren’t department stores. They’re grocery stores, restaurants and other establishments that fit into the fabric of everyday life. “Take the Great Punjab Business Centre,” she says, citing the South Asian-focused plaza that opened a few years ago off Mississauga’s Airport Road. In theory, she says, people would head to one of the many mosques or Sikh temples within a few minutes’ drive of the shopping centre to worship, then go to the mall for lunch.

There is also the slow and silent, market-driven way these developments transform themselves.

“It’s so interesting to look back to the late ’80s when the site of Pacific Mall used to be a country farm that was a popular tourist attraction,” Zhuang says.

Long before the Asian megamall opened in 1997, Cullen Country Barns occupied the land at Kennedy Road and Steeles Avenue East. When the Market Village shopping centre was built next door in 1990, it too displayed a rural market theme. But visitors soon lost their appetite for rustic trappings and the businesses suffered, she says.

By 1994, Cullen Country Barns had closed its doors, while Market Village was filling up with Chinese storeowners.

“It was a case of Market Village being developed by mainstream developers, but the businesses were leased to individual entrepreneurs,” Zhuang says. “The market actually speaks to the needs of the Chinese community at the time. Without these [Chinese] businesses, the mall would have closed.” When it works well, says Zhuang, this type of retail growth is a perfect example of adaptive re-use.

Although development format might dictate how a neighbourhood engages with a retail area—people would conceivably spend an entire afternoon in a mall, but likely not in a business park—Zhuang is particularly interested in how suburban ethnic retail could evolve as demographic patterns and business owners’ relationships with municipal governments start to shift.

As The Globe and Mail reported in 2012, ethnic mall-style developments might be catching up to changing consumer habits. Developers originally announced in 2009 that a project called the Remington Centre would be built on the site of Market Village, but they didn’t release plans for construction until early last year. In the intervening time, the proposed 800,000-square-foot mall has significantly altered its branding from a complex targeted toward the Chinese community to something a little more crossover. The project includes two residential condo towers.

“The message is quite clear that the new development is not just for the Chinese community,” says Zhuang. “That’s a new strategy that I appreciate. We want to promote integration among different communities.”