Acknowledging our own presence in a system that chooses to ignore us is a radical act.

By Liz Ikiriko

This past May, a number of catastrophic, yet unsurprising, tremors shook the art and media worlds in Toronto and Canada, exposing the shifting state of Indigenous and racialized representation.

In front of Metro Hall, photographer Jalani Morgan’s images of black power and protest (on public display for the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival) were slashed and vandalized. Because such an act of disrespect is not new – because it was expected – Morgan, along with artist Syrus Marcus Ware and curator Emelie Chhangur, planned and used this opportunity to enact a heartfelt response in the face of attack. They carefully stitched the damaged canvases with red thread. Publicly highlighting the wounds and emphasizing the loving concern we — racialized and Indigenous beings must practice for our survival.

Then, ten Indigenous writers were openly insulted by Write magazine, when editor Hal Niedzvieki opened a special issue dedicated to Indigenous writing with an editor’s letter suggesting the creation of an “appropriation prize” to be given out to writers succeeding in writing from other cultures viewpoints.

That first shock caused a ripple effect, spurring the white media elite — editors, columnists and execs from CBC, Rogers, Macleans, the National Post and the Walrus to respond in enthusiastic, glib agreement. This flippant response was devastating for many of us in the media, hard proof that our work, our perspective is not truly valued by the people cutting our cheques. In a landscape that has only recently begun to acknowledge the lack of diversity within the ranks, the dismissive boldness of these actions were a painful realization.

Our social, online world is dizzying, yes. But it also offers opportunities to create new paths, to have different, more promising conversations than what the mainstream continues to offer us. To quote CBC’s Indigenous and pop culture correspondent Jesse Wente, who had an empowering, emotional response to the appropriation prize hoopla: “We can do this in another way and that is not going to change.”

This is the reality that shakes the mainstream. Even as we are surrounded and inundated by media without our permission, we can also create our own images, ideas and stories, and anchor ourselves to them.

In 1990, artist Buseje Bailey (who is featured in this issue’s portrait series Light Grows the Tree) was asked how she makes room in her life to create her art. She replied: “When I breathe, there is a space. Under my ribs someplace. So I make room there.”

Our Visual Issue is about making space for ourselves. The simple acknowledgement of our presence within a dominant system that chooses to ignore us is a radical act.

We are a small crew at The Ethnic Aisle, and our anxieties are tested between work, family and maintaining this platform. A few weeks ago, we announced our intention to go on hiatus, but this past month has led us to reconsider. This is not the time for pause. So instead, we request your help. If you’re not yet a donor, please consider giving us a few dollars so we can pay creators who long for something else. If you have editing or art department skills that you could donate a few times a year, please let us know. We need to grow to survive.

As anxiety-inducing as this age is, it is also a time that exposes our scars that highlight our achievements and fuels the path forward. We hope that we have offered you new ideas and a place to rest in the past, and we want to continue doing so in the future.

Banner photo - Repairs to Jalani Morgan's exhibition "Sum of All Parts" on view in front of Metro Hall during the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, May 2017

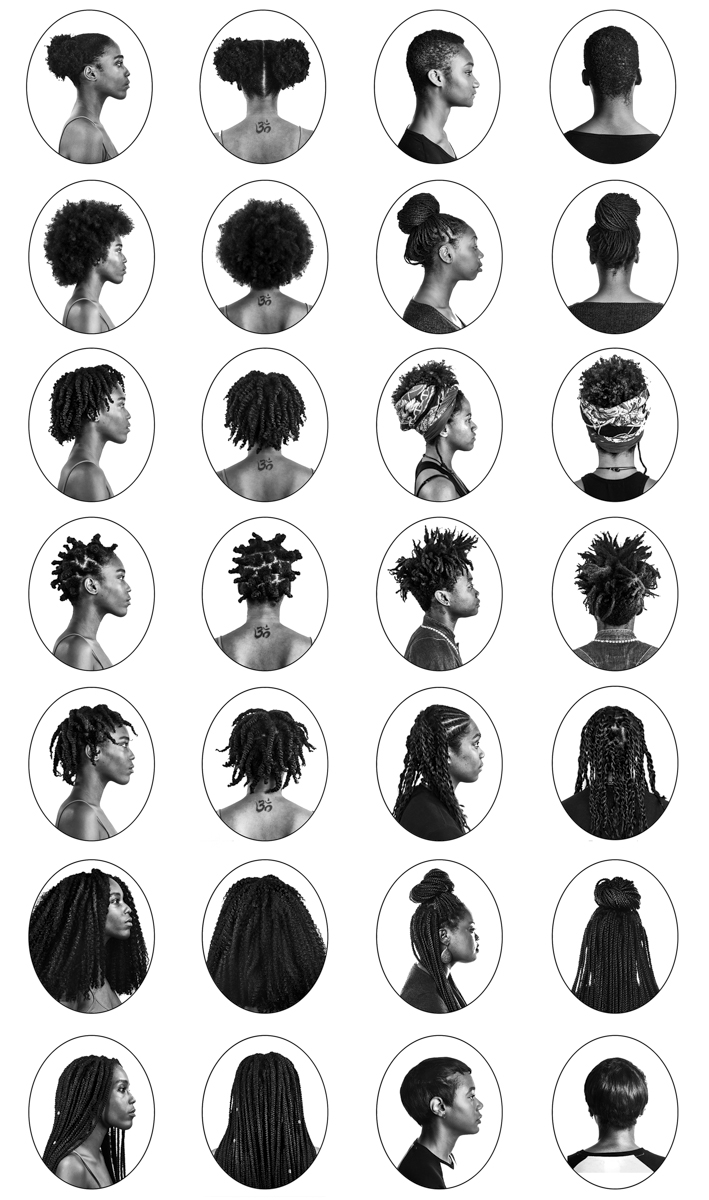

"There is such rich nuance to Blackness here: it is no single thing." Documenting a community of Black artists, writers, curators and collectors in Toronto.