Flesh and blood: Filipino dinuguan, my dad and me

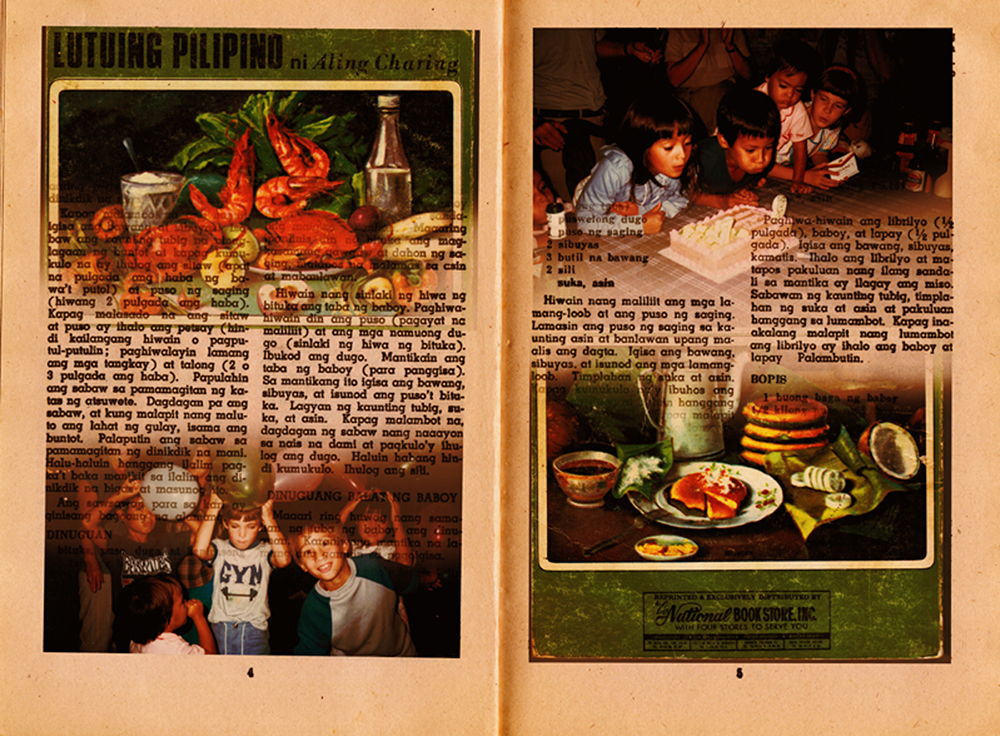

/Photo Illustration by Amada Estabillo

By Amada Estabillo

“We be of one blood ye and I.” These are the master words of the jungle taught to Mowgli by Baloo, giving him protection from “the birds and the snake people and all that hunt on four feet except his own pack.” Growing up, I read and reread Kipling’s Jungle Book. It seems like a weird choice for a fourteen-year-old girl from suburbia. I guess I liked their strict code of honour. Above all I liked Mowgli, an outsider who made his way with the wolves and lived by his wits. He had no one that was truly of the same blood, no human relative or friend.

We all set great store by the idea of being bound by blood, by the blood we share with our family, or with a particular people. What happens when our connection to the people with whom we share blood is severed? Can you be an outsider within your own culture? How do we learn our own master words—and who can teach us?

One of the things that I’ve long associated with my dad is cooking. I can still picture him at the stove, frying chicken or roasting marinated pork, with his thatch of Bruce Lee-style hair and thick mustache. He had a great sense of humour, and would cook and socialise at the same time. I have memories of my little brother by his side, learning to chop vegetables when he was only 3 years old.

When I was 11, my dad died of cancer. He was my Filipino half. I did have a large supportive family on my mother’s side, but it felt to me it as if a bridge to my dad’s side became somehow impassable. Long after my he died, when I was in my twenties and living in Vancouver, I awoke in the night from a vivid dream about him, the smell of the rice cooker running in the kitchen stirring old memories. Ever since, our small repertoire of Filipino dishes became a way to stay connected to his memory. These days, my brothers and I will email or text about the correct ratios for soy sauce to vinegar for chicken adobo, and whether to add bitter melon or coconut milk.

As a kid we always had huge family gatherings, every holiday, birthday, weekends. We were an Irish-American family that had intermarried with an extended family of Filipinos. Because of this, our parties included a strange mix of chips, pop, and processed foods combined with Filipino staples: chicken or pork adobo, a dish of meat, soy sauce and vinegar; stir-fried pancit noodles; fried spring roll lumpia; and empanadas.

But the one dish that none of us as children could be compelled to eat was dinuguan, or chocolate meat, as we referred to it. It appeared suspiciously dark, gravy-like—not chocolate at all. It is in fact a stew, found in many countries in different guises actually going back to the time of Homer, comprised of both offal and blood. The name of the dish comes from the word dugo, Filipino for blood. I never sampled it, and neither did my siblings. Among my cousins, to eat dinuguan was to win a dare — not to savour a favourite dish.

Over time our family get-togethers changed, spread further apart and encompassed fewer of us. My ties to the food at those gatherings became more tenuous as time passed. Any Filipinos I met during university would greet my ethnic claims suspiciously (in appearance I favour my white mother) until I mentioned adobo or lumpia or another favourite Filipino dish and then, the password having been spoken, the doors opened. My brothers became adventurous cooks, smoking meats, deboning fowl, stuffing roasts, making head cheese.

I am not such an adventurous cook, but I am an avid eater. Not too long ago, I proposed a Filipino feast to my brothers: we would venture to the GTA and sample a meal of lechon, a southern Filipino tradition introduced by the Spanish during colonization eating a whole roast pig. We would have it with various sides, including the infamous dinuguan.

Photo Illustration by Amada Estabillo

Dinuguan was not easy to track down . I scoured online reviews and menus for buffets and dive-y take out places alike. I wondered if maybe it is more of a comfort food than a dish that is routinely prepared at restaurants. It was also difficult to find a night when both my brothers, and our respective partners and families were free at the same time. Holidays passed; some places closed between Christmas and New Year. I chose three places where I was sure I could get the blood soup: Tita Flips, a food stall at Bathurst and Dundas; Lamesa, a new restaurant on West Queen Street West that listed an interesting combination of pork and octopus dinuguan; and Pook Ni Butchukoy, a tiny take out place at King and Dufferin.

The big evening finally comes. One takeout place doesn’t have the dinuguan ready that day, and the new local place switched their menu over and was offering beef cheek instead. I feel a panicky despair growing quickly being displaced by guilt. Should I have opted for the kamayan; the big whole pig feast with all the family? But now it’s too late; my brothers are on their way. I stop at Tita Flips, where an older “tita” is running the stall. I order the blood soup, some marinated beef tapa for my daughters, and two orders of pork lumpia. My panic subsides as the older woman moves pots between hot plates, alternately stirring and shaking the meat. She ladles the dark stew into a styrofoam soup container with a plastic lid. Maybe it’s the careful way she packs my spring rolls in paper to keep them crispy, or how she stacks the containers in the plastic bag so that nothing will spill, but watching her prepare the foods I am inexplicably comforted.

The car fills with the aroma of my childhood. At home I fry some eggs while my daughters fight over the lumpia, asking me why they couldn’t eat this for lunch every day. (Although they love adobo and pancit, the tiny, precise spring rolls always seemed too time-consuming to make.) Although I introduce it as beef stew and don’t mention the ingredients, they will not try the dinuguan. Their response mirrors my own at that age: suspicion.

When my brothers arrive we sit down together. It isn’t the sophisticated tasting I had envisioned, nor the big celebration with the wider family it could have been. But seeing them like this, side by side, I can see permutations of my dad and also of me. The black hair, brush-like on one brother, the mustache; transformed into a short beard on the other brother. Our dark eyes all the same.

We dish the dinuguan from the humble takeout container over the pancit noodles, as the girls have eaten all the garlic rice. It’s the same thick, dark colour that I remember. There is a chalky look to the sauce and my middle brother points out that it clings to the bowl in a different way than gravy or fat, marking it out as blood. My brothers dig in immediately but I hesitate, my old prejudices rising up.

But the aroma is good: adobo-y with soy, garlic and vinegar. There are chiles mixed in with the meat. I taste a mouthful. Instead of the coppery flavour of liver that I expect, there is rich and tender meat and spice. Both the boys agree that it’s good. They are surprised too, comparing the flavour to blood sausage, describing the dinuguan as more subtle, less dense. It doesn’t taste bloody at all to me, though it is heavy. One of my brothers says that it is more in the after taste or the feel of the sauce in your mouth that you notice it and we all agree. Soon we have finished the bowl.

In the end the dinuguan is both more, and less, than I thought it would be. It tasted better than I expected, but that isn’t important. We may inherit our blood, but we build our own connections; one way we keep them alive is by cooking and eating and remembering together. I had thought the dinuguan would reveal something to me, and in one way I guess it has; it’s reminded me I have the master words to my familial language already. I just didn’t realize it.

In this case, the master words are the dishes shared between people who care about each other, dishes prepared by strangers who extend something of themselves each time they cook for someone new. These master words are available to us all. If we are interested and open we can speak to each other, discovering or rediscovering the stories of those around us through a common language we can all understand: the language of food.